IN THIS ARTICLE: Many Christians labor under the misconception that there were no women apostles and that women could not be apostles. But Paul greets a woman named Junia, and calls her an outstanding apostle, in Romans 16:7. Properly understanding this verse has implications for how the church family operates today.

Contemporary scholars debate nearly every word of Romans 16:7 because it contradicts the idea that women must not hold authoritative positions within the church. Yet verse seven fits within a section that shows Paul’s approval of several women in leadership.

Romans 16 closes Paul’s longest letter with a commendation and greetings, typical of letters in the Greco-Roman world.1 Given that Paul has never been to Rome, the list of greetings “functions as a recommendation for Paul himself, presumably showing him to be both well-informed and well-connected.”2 The length and subject matter of this letter show that Paul regards the Roman house churches to be essential, so Paul must end his letter well. Amid this ending, he writes:

Greet Andronicus and Junia, my fellow Jews who have been in prison with me. They are outstanding among the apostles, and they were in Christ before I was. – Romans 16:73

Although Romans 16 is vital for his credentials, he feels no need to refrain from commending this woman, Junia, as a leader (alongside eight more named women and several who go unnamed). Everything is in service to the gospel, so for Paul, it’s all hands on deck: slaves, free, Romans, Greeks, Jews, women, and men. Romans 16:7, and chapter 16 more broadly, shows that the church needs women on the front lines and in the strategy rooms, now as in the beginning. We will see that nothing in Paul’s methodology prevents this.

Rom. 16:7a – “Greet Andronicus and Junia”

Paul asks his Roman audience to greet two apostles, possibly a missionary couple like Priscilla and Aquila, whom he introduced in 16:3-4.4 One bears the masculine name Andronicus. The other is Junia, a popular feminine name attested on 250 ancient inscriptions in Rome alone.5

Early in the twentieth century, English translators gave her name a masculine ending, Junias, speculating it to be a diminutive form of Junianus, a common male name. But there is no record of any shortened form of Junianus, nor any evidence anyone ever bore the name Junias—no inscriptions, literary works, or documentary sources.6

Over the last three decades, the tide has turned so that few scholarly proponents of a reading of “Junias” remain, thanks to the work of scholars like Eldon Epp, whose basic case includes the following data points:

Junia was a popular Roman name

Christian authors of late antiquity exclusively rendered the accusative Ἰουνίαν of Romans 16:7 as Junia (as do all the early translations: Old Latin, Vulgate, Sahidic and Bohairic Coptic, and Syriac)

No one has discovered real-world examples of the hypothetical masculine forms

and English translations from Tyndale (1526/34) to the last quarter of the nineteenth century all acknowledge the feminine Junia except for Dickenson’s 1833 translation.7

Why the attempted change to a masculine name? Lynn Cohick writes,

The answer lies in the committees’ convictions that a female apostle was unlikely, and so this name Junias—unknown throughout the Greco-Roman world—was created ex nihilo to match their presuppositions.8

The men behind the attempted name heist were late to the party, given the universal acknowledgement of the feminine form by early Koine Greek [New Testament Greek] speakers like

Origen (ca. 185-254)

Ambrosiaster (ca. 375) (who uses “Julia,” a variant in five ancient copies of Romans, the earliest being Papyrus 46)

Ambrose (339-397)

John Chrysostom (ca. 344/354-407)

Jerome (ca. 345-419)

and Theodoret of Cyrrhus (ca. 393-ca. 458).9

Epp acknowledges two alleged exceptions. The first, Rufinus’s translation of Origen, carries little weight because the variant Junias appears in just two twelfth-century copies of this document from the same subgroup of manuscripts (in other words, somebody who lived over 1000 years after Origen made a boo-boo, accidentally or intentionally).

John Piper and Wayne Grudem claim to have found the second in a search of the writings of Epiphanius (315-403), although “as Piper and Grudem themselves confess, in commendable candor, ‘We are perplexed about the fact that in the near context citation concerning Junias, Epiphanius also designates Prisca [Priscilla] as a man mentioned in Romans 16:3, even though we know from the New Testament that she is a woman.’ So although Junias is represented in Epiphanius as a male … the credibility of the witness is tarnished.”10 Further, Richard Bauckham shows that the reference is unlikely to belong to the fourth-century Epiphanius, and may have been attributed to him for the first time as late as the ninth century.11

Rom. 16:7b – “my fellow Jews”

Paul describes Andronicus and Junia (and six others in Romans 16) as συγγενεῖς μου, most literally “kin” but rendered by the NIV as “my fellow Jews.” Bauckham12 agrees with most scholars on this interpretation. Junia was a prestigious Roman family name. Freedmen and freedwomen, Jewish and otherwise, often adopted their patron’s clan name as their Latin name, so Junia could have been a Jewish freedwoman or descendant of one.13

However, Jews also often adopted Greek or Latin names that sounded similar to Semitic names (like the sound equivalence of the Greek “Simon” to the Hebrew “Simeon” and the Latin “Annia” to the Hebrew “Hannah”).14 Bauckham suggests Junia is equivalent to the Hebrew Joanna (Yohannah), the name of a disciple of Jesus from the early days of his ministry (Luke 8:1-3) who later witnessed and proclaimed the empty tomb (Luke 24:1-10).

If Joanna is Junia, it would accord with Junia’s apostolic designation (we’ll cover what “apostle” means in part three of this series). Other Jewish members of Paul’s entourage who adopted Greek or Latin sound-equivalent names when ministering in the diaspora include Silas/Silvanus and Joseph/Justus Barsabbas.15

We must also consider that Joanna was “the wife of Chuza, the manager of Herod’s household” (Luke 8:3). It made sense for Palestinian Jews within Herod’s aristocracy, like Joanna, to take Latin names, and it would have made sense for Joanna to become a missionary to Rome later.16 Andronicus could be Chuza’s adopted Latin name, or perhaps by the time Paul writes Romans, Junia/Joanna has remarried. Unless new evidence comes to light, we cannot prove that Joanna is Junia, but nothing disproves it. The hypothesis makes sense.

In 2008, complementarian Al Wolter proposed that Junia could be the Hellenized Hebrew masculine name Yehunni.17 But Wolters admits in his final footnote that Ἰουνίαν is more likely the Latin feminine “Junia.”18 And in 2020, Yii-Jan Lin noted that a Jewish man named Yehunni would not likely choose a Hellenized name nearly identical to a feminine Roman one (this makes me wonder if Lin has heard Johnny Cash’s song, “Boy Named Sue”). In the highly patriarchal world of the Roman Empire, how likely is it that a man would pick a name for himself that sounded like it belonged to a woman?

Lin then asked why no one questions whether Andronicus derives from a feminine Hebrew name: “If this seems a ridiculous question because clearly this Jewish man was given or adopted a well-attested Greek masculine name, then why should IOYNIAN (the Greek “Junia” in the accusative form) need any further explanation than that she is a Jewish woman with a well-attested Latin feminine name?19

Nevertheless, Wolters’s fellow complementarian Esther Ng claims his hypothesis is persuasive. She says that Yehunni is an attested Jewish masculine name, but the popular feminine Latin name Junia is unattested “for Jewish women who lived in the first century.”20 However, Wolters admitted that Yehunni could be a woman’s name.21 Further, we only have two records for the name “Yehunni.” This makes Priscille Marschall wonder why Ng dismisses Bauckham’s Joanna hypothesis:

Not only the Latin name Iunia (Ἰουνία in Greek) is well-attested while Iunias (Ἰουνιᾶς in Greek) is not, but also the Hebrew female name Yeohanna/Joanna is far more attested than Yehunni.22

The scholarly consensus has rightly rejected Wolters’ hypothesis.

Rom. 16:7c – “who have been in prison with me.”

Paul’s Romans 16 greetings bear evidence of the struggle between God’s army and Satan: Priscilla and Aquilla “risked their lives,” and Andronicus and Junia “have been in prison with me.”23 The concept of a cosmic battle with Satan helps explain Paul’s use of συναιχμαλώτους μου, usually translated in English as “fellow prisoners.”24 The term refers to war captives rather than resident criminals.

Paul applies it to Aristarchus (likely a Gentile) in Colossians 4:10 and Epaphras (definitely a Gentile) in Philemon 23, so Paul is not using συναιχμάλωτος to mean “a fellow Jew in the diaspora.” Nor would Paul apply it to only four people if it were a figurative term for Christians. Bauckham writes:

While referring to literal incarceration, Paul uses a word that also interprets this fate as an event in the battle in which he and his coworkers are fighting as fellow soldiers of Christ …. The shame associated with imprisonment in the ancient world is transformed into the honor of a soldier who had stood his ground, refusing to retreat, and had been captured.25

Paul, who had once “dragged off both men and women and put them in prison” (Acts 8:3), is now honored to say that, like Junia and Andronicus, he has been imprisoned for Christ.

Roman authorities only imprisoned women on serious charges, preferring to hand them over to their husbands or family of origin for discipline in most cases. Nijay Gupta finds that most of the crimes for which women could be imprisoned would not have been commended by Paul (theft, temple robbery, murder), and others would not have led to Junia’s eventual release (treason, spreading dangerous philosophies).

This leaves two potential crimes, and they are the crimes Paul seems to have regularly been charged with: civil disturbance and inciting a riot.26 Junia was likely doing what Paul was doing – preaching Jesus as Lord to all who would hear her, which created enough of a disturbance for her to be jailed. Prison would have been an unlikely consequence if she had given private Bible lessons to women and children at home. No, Junia was agitating for Jesus in public.

Roman detention facilities were vile, and the few women who landed there were confined with men. Gupta surveys ancient sources like Cicero, Calpurnius Flaccus, and Diodorus Siculus,27 who described horrific conditions for prisoners, concluding, “For Junia to continue to do public ministry, knowing firsthand the risks, was astonishing.” No wonder Paul’s next phrase singles out her and Andronicus for high honor.28 29

Coming Up:

Next Monday, I will show that Junia and Andronicus were not merely “well known to the apostles” (as translations like the ESV claim) but truly “outstanding among the apostles.” If someone tells you, “Well, Junia could have been a woman or a man, and she could have been an apostle or well-known to them,” I want you to realize that the people who make these claims are those with a vested interest against the possibility of a woman apostle because of their presuppositions about women. Their arguments are a series of long shots. Next week, we’ll see what a long shot the “well-known to the apostles” argument is.

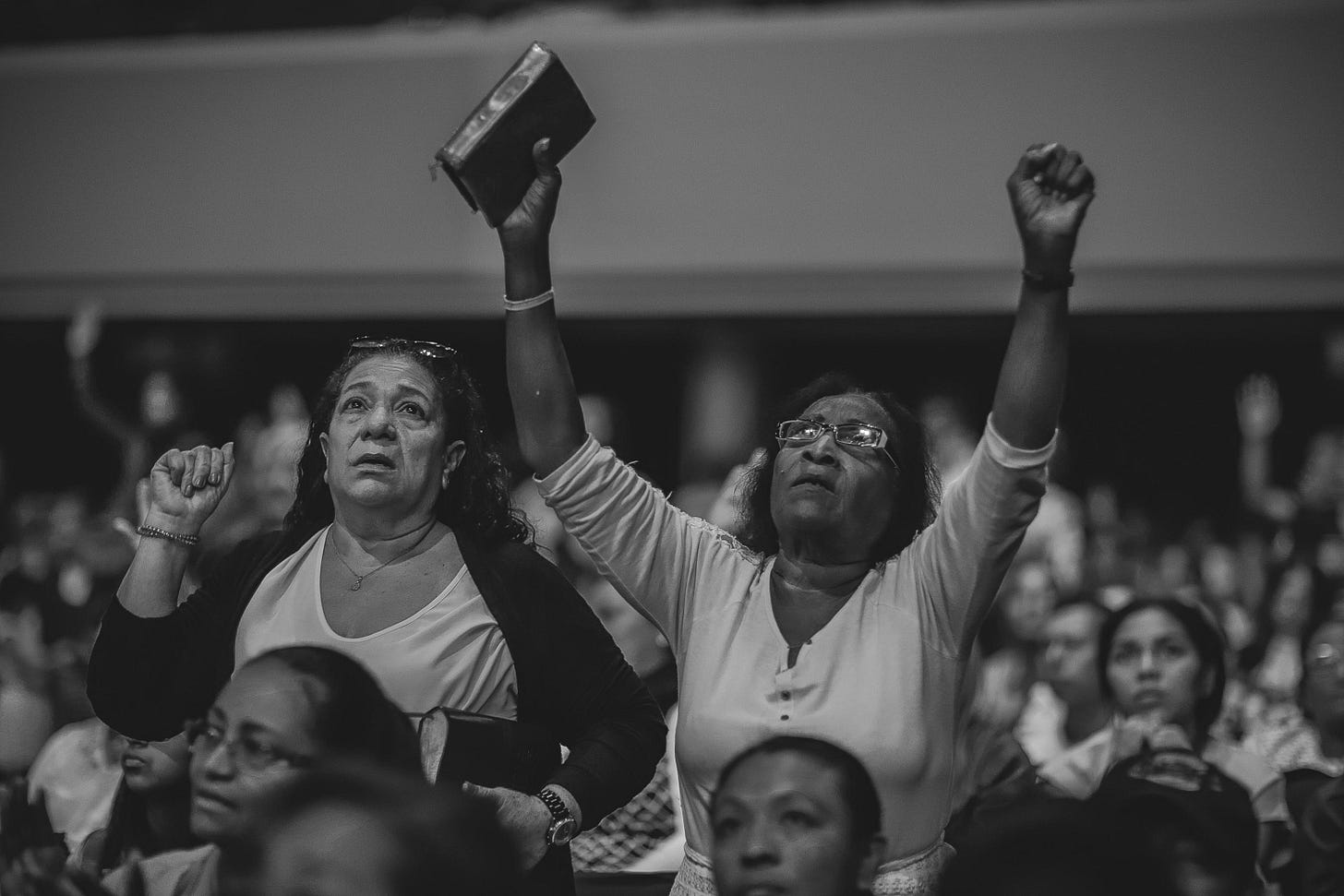

In the meanwhile, know that the male translators who attempted to remove Junia from scripture — metaphorically “killing” her — have failed. We need to talk about Junia, and we need to celebrate her many spiritual daughters down through time and into our day.

Junia is not alone. She’s accompanied by a host of women who have been gifted by God to teach and preach and lead.

And now it’s time for you to do something about it.

— Scot McKnight30

Want to drop a comment to say, “This must be wrong because of 1 Timothy 2:12” or “the Genesis created order?” First, please see my articles about 1 Peter 3:1-7, Ephesians 5, Genesis 1-3 (here and here), and 1 Timothy 2:11-15 (quite a few articles, including here, here, here, here, and here).

Beverly Roberts Gaventa, Romans: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2024), 426.

Katherine Grieb, The Story of Romans: A Narrative Defense of God’s Righteousness, First Edition (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 144.

Unless otherwise indicated, all Bible references in English are from the New International Version (NIV).

Grieb, The Story of Romans,144–45.

Priscille Marschall, “The Junia Case, Once Again. A Response to Esther Yue L. Ng, ‘Was Junia(s) in Rom 16:7 a Female Apostle? And so What?’” Journal of the European Society of Women in Theological Research, Sept. 19, 2023: 4-5.

Lynn H. Cohick, Women in the World of the Earliest Christians: Illuminating Ancient Ways of Life, 1st edition (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009), 215-16.

Eldon Jay Epp, Junia: The First Woman Apostle (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 23–25.

Cohick, Women in the World of the Earliest Christians, 216.

Epp, Junia, 32–34.

Epp, 33–34. Further, Michael Burer and Daniel Wallace acknowledge the superiority of the evidence that Origen thought Junia a woman. See Michael H. Burer and Daniel B. Wallace, “Was Junia Really an Apostle?: A Reexamination of Rom 16.7,” New Testament Studies 47 (2001): 76-77, esp. fn3.

Richard Bauckham, Gospel Women: Studies of the Named Women in the Gospels (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 166–67.

Bauckham, 170.

Bauckham, 169.

Bauckham, 182–83.

Bauckham, 184–85.

Bauckham, 185–86.

Al Wolters, “ΙΟΥΝΙΑΝ (Romans 16:7) and the Hebrew Name Yehunni,” Journal of Biblical Literature 127 (2008): 397–408.

Wolters: 408.

Yii-Jan Lin, “Junia: An Apostle Before Paul,” Journal of Biblical Literature 139, no 1 (2020): 193-94

Esther Yue L. Ng, ‘Was Junia(s) in Rom 16:7 a Female Apostle? And so What?” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, 63/3 (2020): 522.

“Al Wolters responds on Junia” in the “Paul and Co-workers” blog of Richard Fellows. Accessed May 14, 2025. https://paulandco-workers.blogspot.com/2011/02/al-wolters-responds-on-junia.html

Marschall, “The Junia Case, Once Again”: 8.

Beverly Roberts Gaventa, Romans: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2024), 441.

Despite the NIV’s translation “in prison with me,” the grammar doesn’t prove whether Paul was in prison at the same time and place as the pair, just that the three apostles share the status of those imprisoned for Jesus Christ.

Bauckham, Gospel Women, 170–71.

Nijay Gupta, “Reconstructing Junia’s Imprisonment: Examining a Neglected Pauline Comment in Romans 16:7.” Perspectives in Religious Studies, 47 no 4 Winter (2020): 391.

Gupta, 392-93

Gupta, 397.

If you don’t have access to a theological library, you can see Gupta’s argument in his chapter on Junia in Tell Her Story: How Women Led, Taught, and Ministered in the Early Church (Grand Rapids: IVP Academic, 2023), 141-52

Scot McKnight, “Junia is Not Alone” from The Blue Parakeet, 2nd Edition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2018), 304.

Wow!!! That was amazing - so incredible. My favorite line:

“Prison would have been an unlikely consequence if she had given private Bible lessons to women and children at home.”

Brilliant! I am still grinning shaking my head and occasionally fist pumping. That one hits - nice work, Bobby!

Junia is one of my faves! Thank you for writing about her!