Do We Read Scripture Like Enslavers? How A Flat Reading Harms

I have been wanting to write an article about how “the Reformed and literal hermeneutic proved inadequate to address the injustice of chattel slavery in America,” which is a sobering example of how a “‘flat’ or literalist reading of the Bible, and Paul’s letters in particular, can be wielded by the powerful to harm and/or preserve the status quo.” Then I discovered that my friend Jane Anne Tucker had already done so, better than I could.

I met Jane Anne as part of our wonderful New Testament cohort at Northern Seminary. I’m so glad she’s allowed me to publish the article below, which she originally wrote as a paper at Northern. You’ll find Jane Anne’s bio at the end of her excellent article:

Paul and Nineteenth-Century Proslavery Hermeneutics

Almost all contemporary American evangelicals agree that Christianity is incompatible with pro-slavery ideology. But the lack of “chapter and verse” proof to support this conviction has complicated discussions about slavery and the New Testament.1 The apostle Paul addressed both enslaved people and their masters,2 and he regularly used slave imagery in a positive and negative sense.3 However, Paul lived in a “slave society,”4 a society devoid of the abolitionist convictions that Christians now widely share.5 This “collision” of modern and ancient worldviews has created interpretive tension for contemporary readers of Scripture.6

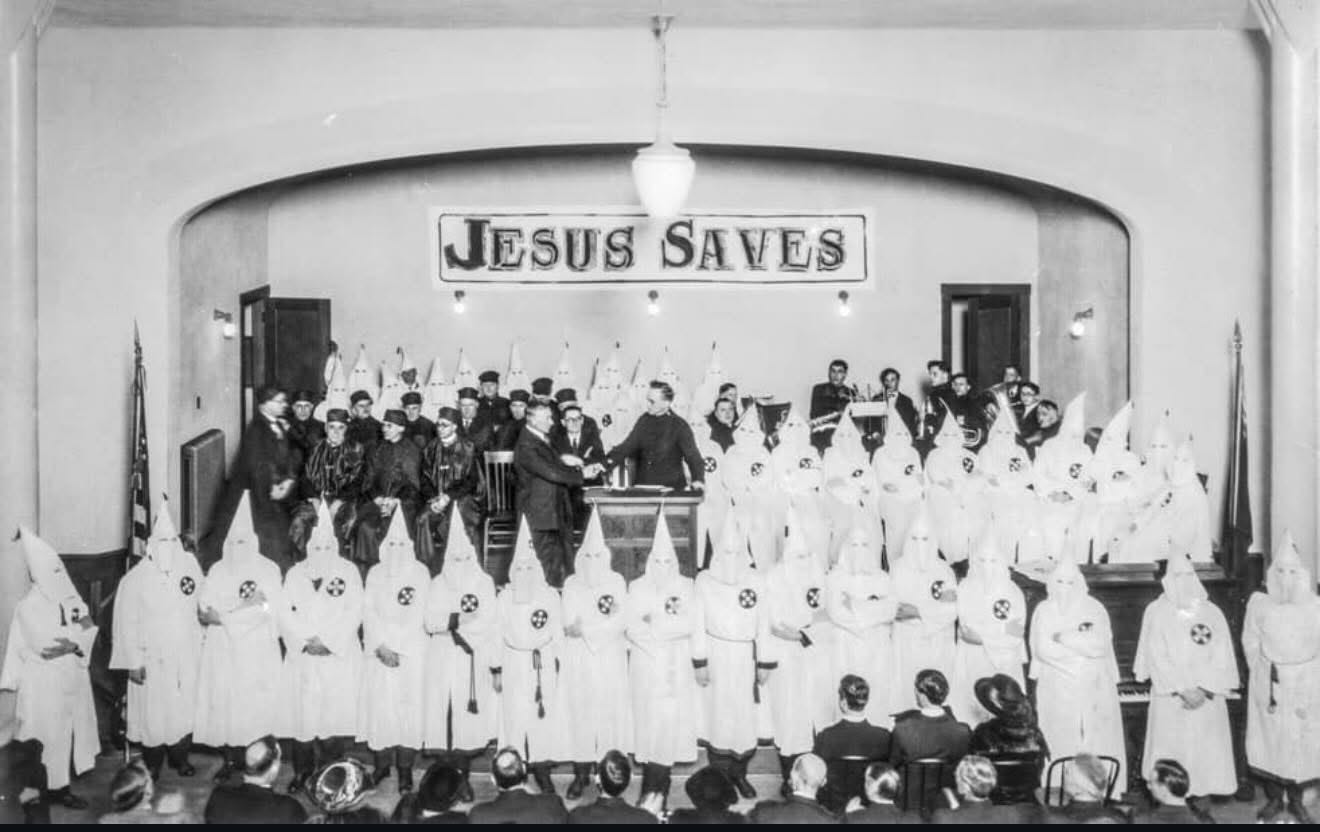

Christianity’s connection to the horrific legacy of New World slavery has significantly increased this tension and profoundly influenced the study of Paul and slavery.7 Tragically, Christians were not bystanders to the “moral collapse” of slavery; many ministers and laypeople actively participated in and defended the institution of slavery.8 In response to growing antislavery sentiment in the Northern states and Europe, nineteenth-century American theologians and ministers used the Pauline corpus to justify slavery as a Christian practice.9

Proslavery theologians produced a highly potent argument that framed the debate over slavery as a “forced dichotomy—either orthodoxy and slavery, or heresy and antislavery.”10

By the 1850s, an increasing number of white American Christians believed “what almost no Protestants elsewhere in the world still believed—that…the Bible did in fact sanction slavery.”11

Why was proslavery theology so well-received in the United States? Many factors contributed to its popularity; obviously, prior commitments such as racism and economic greed played an indispensable role. But in the end, the proslavery argument was devastatingly effective for another reason: leading proslavery Christians successfully employed the prevailing method of interpreting Scripture (i.e., the dominant hermeneutic) to brand the abolitionist cause as dangerously unbiblical.

The Dominant Hermeneutic in Nineteenth-century America

Historian Mark Noll describes pre-1865 America as a “Bible civilization.”12 The Bible exerted a powerful influence on the religious, legal, and social structures of society; Noll also notes the “casual regularity with which antebellum Americans salted their day-to-day communications with the Bible.”13 Sermons were the “most witnessed form of public speech” in antebellum America, and Scripture was rigorously studied in esteemed seminaries such as Princeton and Andover.14

The highly noted conservative theologians who conscientiously defended the authority of Scripture in the nineteenth century15 employed a “Reformed and literal” hermeneutic.16 “Reformed” refers to the Calvinist traditions (Puritans, Presbyterians, and other Reformed communities) that shaped the early American approach to the Bible.17 These traditions defended the principle of sola scriptura in all matters: Scripture not only teaches the way to salvation, but it also provides a definitive guidebook for everyday life.18

Notably, the growing spirit of “antiformalism,” “antitraditionalism,” and “democratization” during the Revolutionary era and early decades of the nineteenth century intensified Americans’ trust in sola Scriptura relative to their European counterparts.19 Reliance on the “Bible alone” permeated the culture; in this context, “a suspicion that other authorities besides biblical chapter and verse were not just secondary but dangerous” thrived.20

At the same time, the hierarchical and traditionalist values of the Old World were increasingly displaced by a spirit of “democratic individualism”21 and a belief in the commonsense intuition of the individual to discern the plain meaning of Scripture. This American penchant for commonsense literalism thus paved the way for a “distinctly American form of Biblicism.”22

Whereas early Reformed interpreters had produced sophisticated theological syntheses in which some texts could be elevated over others,23 confident and empowered Americans believed that they could clearly apprehend the meaning of Scripture without external guidance.24 Put simply, Americans possessed an overarching belief that “God’s intentions were clearly expressed in the Bible and readily available to all.”25

The Reformed and Literal Hermeneutic in the Slavery Debates

Because Scripture permeated all aspects of society, the Bible was a primary player in the slavery debates.26 Assisted by a Reformed and literal approach to the Bible and a deep trust in their commonsense intuition, many Americans easily concluded that Paul did not condemn slavery; rather, he appeared to accept the institution and even provided instruction to slaves and slaveholders. Unsurprisingly, many white Christians directly applied the Pauline household codes to American slavery. The command for slaves to obey their masters served as a “clinching piece of evidence that the rules of morality in this area had not changed.”27

Paul’s decision to return a runaway slave to his owner, as recorded in the letter to Philemon, was seen as further proof that Paul respected the property rights of slaveowners. Horrifically, the book of Philemon was further exploited to justify the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a law that empowered and financially incentivized citizens to apprehend runaway slaves or even kidnap free blacks to sell into slavery.28 This Pauline evidence, filtered through the predominant hermeneutic, resulted in a severe critique of abolitionism. Proslavery theologians produced a plethora of material— sermons, pamphlets, essays, and books—that disseminated the ‘plain’ evidence from Scripture and exposed the “unbiblical” message of the antislavery movement.29

While traveling in the United States in 1857, Englishman James Stirling read an example of this proslavery literature, Albert Taylor Bledsoe’s Essay on Liberty and Slavery. Although Stirling himself was unsympathetic to the institution of slavery, he was astonished by the very force of the proslavery apologetic in the American context:30

A large portion of Bledsoe's book is devoted to the Scriptural argument in favour of slavery; and here, I must confess that, as against his opponents, the orthodox Abolitionists, he is perfectly triumphant…The express recognition of slavery….and the precepts for the behaviour of masters and slaves… in the Epistles of Paul and Peter, are irresistible proofs that the institution was recognised by the founders…of …Christianity. How those who adhere to a literal interpretation of the Bible, and consider every direction contained in its pages as applicable at all times to all men, are to reconcile these facts with modern anti-slavery notions, it is, thank goodness, no business of mine to find out.31

Stirling noted the prevailing belief that the Scriptures apply to every aspect of life. More importantly, as an outsider, Stirling recognized a difference between the belief in the authority of Scripture outside of America and the unique “axioms of interpretation by which biblical authority was apprehended throughout the United States.”32 He concluded that the dominant American hermeneutic inexorably supported the cause of the slaveowner over the Christian abolitionist.

Not all proslavery theologians were Southerners. Charles Hodge of Princeton, one of the most influential theologians of the nineteenth century, had misgivings about slavery as it existed in the South; nevertheless, he was much more alarmed by abolitionism.33 He repeatedly noted in his essay “The Bible Argument on Slavery” that even though Paul had encountered the “worst forms” of slavery during his ministry, he had not condemned slavery.34 The New Testament writers do not speak about the morality of slavery but rather “prescribe the relative duties of masters and slaves.” Significantly, “there is not even an exhortation to masters to liberate their slaves, much less is it urged as an imperative…”.35

Hodge also notes that Paul embraced slaveholders as “Christian brethren.”36 Therefore, slaveholding must be “consistent with the Christian character and profession,” and “to declare it to be a heinous crime is a direct impeachment of the word of God.”37

In 1846, the moderate Leonard Bacon, a Congregationalist minister who also expressed discomfort with slavery,38 delineated the interpretive predicament and potential danger: “The evidence that there were both slaves and masters in the churches founded and directed by the apostles cannot be gotten rid of without resorting to methods of interpretation which will get rid of anything.”39 According to Bacon, abolitionists “torture the Scriptures” to support their cause and thus grievously undermine the authority of Scripture itself.40

Like Hodge and Bacon, John Henry Hopkins, Episcopal Bishop of Vermont, freely admitted his discomfort with slavery. But he, too, was persuaded by the “hermeneutics of plain sense” that it would be sinful to oppose slavery.41 In Hopkins’ Bible View of Slavery, he writes:

If it were a matter to be determined by personal sympathies, tastes, or feelings, I should be as ready as any man to condemn the institution of slavery, for all my prejudices of education, habit, and social position stand entirely opposed to it. But as a Christian, I am solemnly warned not to be “wise in my own conceit,” and not to “lean to my own understanding.” As a Christian, I am compelled to submit my weak and erring intellect to the authority of the Almighty….42

Stunningly, Hopkins’ “plain sense” hermeneutic led him to approve an institution he “intuited to be evil.” According to Hopkins, moral intuition was “unreliable” and perhaps even dangerous. Speaking about Hopkins, Albert Harrill observes that “Proslavery’s biblicism was so extreme as to render rational judgment in debate over moral issues a form of religious infidelity.”43

Lest we shake our heads in disbelief, Kevin Giles suggests that modern interpreters have failed to grasp how “compelling” the pro-slavery arguments were for many white Christians.44 The seeming logic of the proslavery position, as constructed by the dominant American hermeneutic, was clear: The Bible was God’s authoritative word, and if it “tolerated” and “sanctioned” slavery, then “it was incumbent upon believers to hear and obey.”45

Racism

The Reformed and literal hermeneutic employed by many white Americans in the nineteenth century was flawed; it diminished valuable considerations of socio-historical context, genre, and the metanarrative of Scripture, for example. However, this hermeneutic is not the only reason that proslavery theology was highly effective during the decades leading up to the Civil War.

Other commitments, specifically the widespread belief that black people are inferior and deserving of subjugation, were fundamental to the success of proslavery theology.46 The same interpretive confidence that underpinned Americans’ approach to the Bible buoyed their trust in their other (allegedly) commonsense intuitions, including what Noll terms their “intuitive racism.”47 Even Charles Hodge, a meticulous and highly “perceptive” scholar, instinctively integrated racist beliefs into his work while professing to rely strictly on the Bible alone.48

Of course, African Americans recognized the powerful hand of racism. Frederick Douglass correctly noted that no white person “would defend slavery, even from the Bible, but for this color distinction… Color makes all the difference in the application of our American Christianity.” Douglass continued, “The same Book which is full of the Gospel of Liberty to one race, is crowded with arguments in justification of the slavery of another.”49

The Continuing Influence of Proslavery Theology in the Church

We’d like to think that proslavery theology is a relic of the past. However, three fields of study - Greco-Roman slavery, New World slavery, and Paul’s letters - are now “inextricably intertwined” because of how Paul’s words were utilized to defend Southern slavery.50 The Pauline texts that were used to support slavery continue to bear the weight of their interpretive history. Some readers have avoided specific texts altogether or questioned Paul’s directional influence on Christianity.51 At the very least, the legacy of slavery has muddled our collective ability to contextualize Paul’s instructions to first-century slaves and slaveowners and embrace his use of slave imagery to describe humanity, followers of Christ, and Christ himself.52

Christians rightly look to the Bible for wise and ethical guidance. But, as Wayne Meeks asks, what should we do when “an honest and historically sensitive reading of the New Testament appears to support practices…that Christians now find morally abominable?”53 During the slavery debates, some antebellum abolitionists chose to dismiss the authority of Scripture altogether.54 However, there were—and are—other hermeneutical alternatives.

Other interpreters, including Christian slaves and free blacks in the North, received and interpreted Paul’s writings differently. There are numerous examples of both white and black Christians appealing to the redemptive spirit of Scripture’s metanarrative and greater historical consciousness.55 These interpreters were widely ignored due to racism and the controlling narrative that cast anti-slavery convictions as unbiblical.

Driven by a mistaken sense of biblical faithfulness, many theologians did not pursue their misgivings about slavery as it existed in the South but zealously defended slavery in the abstract. Alarmed by abolitionists who dismissed Scriptural authority or abolitionists who simply interpreted the Bible differently, many prioritized the defense of the “authority of Scripture” (but only as they understood it) over the needs of people in bondage. Out of concern for one slippery slope, theologians such as Charles Hodge went headlong down another.56

In the end, proslavery theologians did not defend the authority of Scripture. They defended the authority of their interpretations. Their effectiveness is a sobering example of how a “flat” or literalist reading of the Bible, and Paul’s letters in particular, can be wielded by the powerful to harm and/or preserve the status quo.57

How do we prevent our interpretations from becoming saddled with self-interest and prior commitments? Meeks has suggested the communal practice of “listening to the weaker partner in every relationship of power.” In other words, in the context of the slavery debates, a “fair moral argument” about slavery should have at least included listening to the enslaved. He continues:

whenever the Christian community seeks to reform itself, it must take steps to make sure that among the voices interpreting the tradition are those of the ones who have experienced harm from that tradition…”.58

When a text presents challenging questions or provokes disagreement, it is vital to remain curious about how other groups are receiving and interpreting the text.

Sadly, the Reformed and literal hermeneutic proved inadequate to address the injustice of chattel slavery in America. Neither a Spirit-led theological consensus nor a process of repentance brought about the end of legalized slavery. Legalized slavery was defeated on a battlefield. Because emancipation and the defeat of the Confederacy sidelined the divisive debates over slavery, the hermeneutic that had defended slavery’s legitimacy continued to thrive after the war, albeit with a few more competitors.

In addition, many Americans’ deep-seated racism remained entrenched and found new religious, cultural, and legal expression. As Luke Harlow observed in “The Long Life of Proslavery Religion”, the “beliefs that had sustained slavery” did not magically go away in 1865, but “breathed life into the counterrevolutionary white supremacist order.”59

Over a century later, patterns of unhealthy biblicism and sharp defensiveness over Biblical authority and interpretation remain an identifying feature of American Protestant culture. Perhaps this is evidence of Noll’s hypothesis: to truly understand biblical interpretation in post-Civil War America—for example, how Biblical texts were utilized in disputes over evolution, suffrage, fundamentalism, and segregation—one must look back to the hermeneutic that “fueled the standoff of Civil War.”60

— Jane Anne Tucker

Jane Anne Tucker is a current student at Northern Seminary (MANT). She holds an undergraduate degree in History from Dartmouth College (magna cum laude) and a Master of Music degree from the New England Conservatory of Music. Jane Anne and her husband Louis have lived in Northern Virginia for over two decades and have three young adult sons.

John M G Barclay, “Paul, Philemon and the Dilemma of Christian Slave-Ownership,” New Testament Studies 37, no. 2 (April 1991): 161.

See 1 Cor 7:21-23; Eph 6:5-8; Col 3:22-24; 1 Tim 6:1-2; Titus 2:9-10; Philemon

For example, Rom 1:1, 6:6-22, 8:15; 1 Cor 6:19-20, 7:22-23; Gal 1:10, 5:1, 13; Phil 1:1

J. Albert Harrill, The Manumission of Slaves in Early Christianity (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1995), 42.

Timothy Brookins, “(Dis)Correspondence of Paul and Seneca on Slavery,” in Paul and Seneca in Dialogue, ed. David E. Briones and Dodson, Joseph R., Ancient Philosophy and Religion, Volume 2 (Boston: Brill, 2017), 199.

Harrill, The Manumission of Slaves in Early Christianity, 3.

Byron, Recent Research on Paul and Slavery (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2008), 35.

Scot McKnight, The Letter to Philemon (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2017), 30.

Lisa M. Bowens, African American Readings of Paul: Reception, Resistance, and Transformation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2020), 5.

Mark A. Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 388, 395.

Noll, America’s God, 387.

See Mark A. Noll, America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization, 1794-1911 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

Noll, America’s Book, 122.

Noll, America’s Book, 157.

Kevin Giles, “The Biblical Argument for Slavery: Can the Bible Mislead? A Case Study in Hermeneutics,” Evangelical Quarterly: An International Review of Bible and Theology 66, no. 1 (October 6, 1994): 6, https://doi.org/10.1163/27725472-06601002.

Noll, America’s God, 367–85.

Noll, America’s God, 376-79.

Noll, America’s God, 376-79, 388.

Noll, America’s God, 371.

Noll, America’s God, 376–77.

Noll, America’s God, 382.

Noll, America’s God, 379-80.

Noll, America’s God, 379.

Noll, America’s God, 381.

Noll, America’s God, 384.

Noll, America’s God, 368.

Wayne A. Meeks, “The ‘Haustafeln’ and American Slavery: A Hermeneutical Challenge,” in Theology and Ethics in Paul and His Interpreters, ed. Jerry L. Sumney and Lovering, Eugene H. (Wipf and Stock, 2017), 235.

Lisa M. Bowens, African American Readings of Paul, 113–14.

Noll, America’s Book, 408.

Noll, America’s God, 369.

James Stirling, Letters from the Slave States (J.W. Parker and Son, 1857), 120, http://archive.org/details/lettersfromslav00stirgoog.

Noll, America’s God, 369.

Meeks, “The ‘Haustafeln’ and American Slavery: A Hermeneutical Challenge,” 233.

Charles Hodge, “The Bible Argument on Slavery,” in Cotton Is King, and Pro-Slavery Arguments (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 403.

Hodge, “The Bible Argument on Slavery,” 404.

Hodge, “The Bible Argument on Slavery,” 408.

Hodge, “The Bible Argument on Slavery,” 413.

Noll, Mark, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis, Reprint edition (The University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 45.

Leonard Bacon, Slavery Discussed in Occasional Essays, from 1833 to 1846. (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1846), 180, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008584854.

Bacon, Slavery Discussed in Occasional Essays, 180.

J. Albert Harrill, “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy: A Case History in the Hermeneutical Tension between Biblical Criticism and Christian Moral Debate,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 10, no. 2 (2000): 173, https://doi.org/10.2307/1123945.

Hopkins, John H., “Bible View of Slavery”, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, 2, accessed March 14, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/item/15009288/.

Harrill, “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy,” 173.

Giles, “The Biblical Argument for Slavery,” 12.

Noll, America’s God, 387.

Noll, America’s God, 418.

Noll, America’s God, 396, 418.

Noll, America’s God, 419–20.

Douglass, Frederick, “Douglass’ Monthly”, March 1861, Vol. III, N0. X, 417–18.

Byron, Recent Research on Paul and Slavery, 66.

Bowens, African American Readings, 229-233.

See notes 2 and 3; Phil 2:5-8

Meeks, “The ‘Haustafeln’ and American Slavery: A Hermeneutical Challenge,” 232.

Harrill, “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy,” 159–60.

Harrill, “The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy,” 150-163; Noll, America’s God, See especially the example of Taylor Lewis of Union College on 394; Noll, America’s Book, 530.

Noll, America’s God, 417.

Giles, “The Biblical Argument for Slavery,” 16.

Meeks, “The ‘Haustafeln’ and American Slavery: A Hermeneutical Challenge,” 252.

Luke E. Harlow, “The Long Life of Proslavery Religion,” in The World the Civil War Made, ed. Kate Masur and Downs, Gregory P. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 135.

Noll, America’s Book, 10.

Great Article. Thanks so much for sharing this. I continue to learn more and more about the American Interpretation of the Bible and it is scary how things never change. We lean into verses that justify what we want to believe. I appreciate the writings of those who are debunking this approach to interpreting the Bible.

Your article is very eye opening on a sensitive topic. So very glad the issue has been taken care of with legislation. But it took another 100 years for blacks to get complete and full rights and social acceptance. Too bad that for 100s of years Christians ever used the bible to justify slavery.

What is also shameful is how Christians who are patriarchal/complementarian use the bible today to justify male leadership/authority in the church and have rules that keep women from using their gifts due to there existing no one scripture that outright says women can preach/pastor. Yet a few verses about women (obey, submit, be silent) have been taken out of scripture and have morphed into hundreds of conflicting rules. books, sermons, podcasts, etc on how women should act, dress, limit their education and other micromanaging rules that keep them from education and careers and deeper ministry.

Btu what if slavery were still lawful today. Can you imagine the hundreds of books, podcasts and man made rules that would answer these questions?

can a slave ---

1. pastor or preach ?

2. teach a sunday school class of masters?

3. go to college and have a career?

4. marry their master?

5. say no to their master? What kind of discipline is acceptable for disobedience ?

6. make their own decisions about their life and bypass asking the master to do certain things as led by God?

These questions sound silly, even offensive and a down right waste of time to even think these things. Now substitute women for slave and man for master and you will find out how common these issues are in the pat/comp church today. And the answers are so contradictory depending on which church group is answering them. What is further a black eye in the church is the answer for some extreme groups to #5 is spanking those disobedient wives.

Today the church abhors slavery but winks at women being kept under so many rules and limiting them from finding God's fullest expression for their gifts and service to Him. .